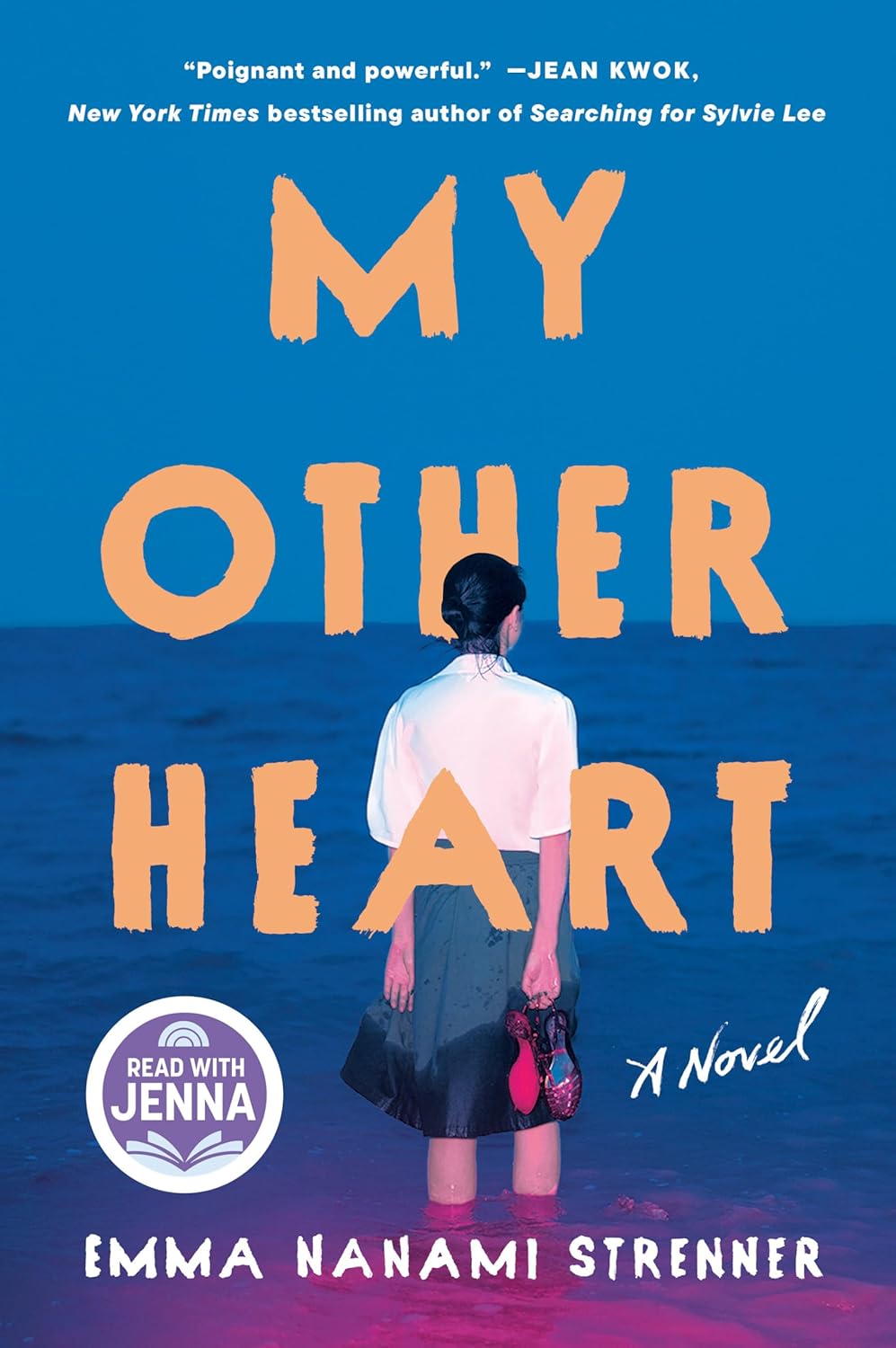

Book Summary

Emma Nanami Strenner’s debut novel My Other Heart weaves together two timelines with emotional precision. In 1998, Vietnamese immigrant Mimi Traung experiences every mother’s worst nightmare when her toddler daughter disappears at Philadelphia International Airport. Seventeen years later, we meet Kit and Sabrina – best friends graduating from high school in affluent Chestnut Hill. Kit, adopted by wealthy white parents, embarks on a journey to Tokyo to connect with her Japanese heritage, while Sabrina, daughter of a Chinese immigrant single mother, navigates class divides and unexpected self-discovery through an internship at an immigration law center.

Strenner’s narrative alternates between these three compelling female voices, gradually revealing how their stories intersect. The novel excels in portraying the microaggressions of being Asian-American in privileged spaces, from Sabrina’s discomfort at country club parties to Kit’s performative embrace of Japanese culture. While the pacing occasionally lags in Mimi’s sections, the payoff is profound when these women’s paths finally converge in Philadelphia, forcing them to confront hard truths about family, privilege, and what truly constitutes belonging.

Key Themes

My Other Heart explores adoption trauma with remarkable nuance, particularly through Kit’s complex relationship with her adoptive mother Sally. Strenner avoids simplistic portrayals, showing both Sally’s genuine love and her unconscious microaggressions (“You’re so exotic looking”). The novel also examines how class shapes immigrant experiences – Sabrina’s mother Lee Lee works menial jobs despite her education, while Kit’s privilege allows her to romanticize her heritage search. Strenner highlights this contrast when Sabrina bitterly observes Kit’s Instagram posts from Tokyo: “She’s collecting cultures like souvenirs.”

The search for identity forms the novel’s emotional core. Kit’s journey to Japan becomes less about discovery and more about confronting her own privilege, especially when she develops feelings for Ryo, a biracial Japanese man who challenges her Orientalist fantasies. Meanwhile, Sabrina’s work with immigration lawyer Eva Kim awakens political consciousness, symbolized by her gradual abandonment of the “model minority” persona. Strenner’s depiction of Mimi’s grief is particularly wrenching, showing how systemic racism compounded her trauma when authorities dismissed her missing child report.

What Makes It Unique

Strenner’s narrative structure stands out by withholding the obvious connection between Mimi and the girls until the final act. This creates genuine suspense as readers piece together clues – the Philadelphia airport setting, Kit’s adoption papers, Mimi’s list of possible daughters. The author also subverts adoption story tropes; rather than a triumphant reunion, Kit’s eventual meeting with Mimi is messy and emotionally raw, complicated by years of divergent experiences and Kit’s privileged upbringing.

The novel’s authentic teen voices set it apart from similar literary fiction. Sabrina’s sarcastic internal monologue (“Another white lady asking if I know Mandarin – newsflash, my mom’s from Fujian”) balances Kit’s more earnest perspective. Strenner captures contemporary adolescent experiences without pandering, from awkward sexual encounters to the performative activism of privileged teens. Some readers may find Kit’s immaturity frustrating, but this serves the narrative – her growth from self-absorbed teen to someone capable of empathy forms the novel’s emotional arc.

Reader Reactions

Early readers have praised the novel’s emotional depth, with one calling it “a magical read that will break your heart then put it back together again” . Many highlight the authenticity of the Asian-American experience, particularly Sabrina’s storyline. As one reviewer noted: “Finally, a book that shows how ‘model minority’ expectations crush actual Asian kids” . The Philadelphia and Tokyo settings also resonate, with readers calling them “characters in their own right”.

Some critiques mention the uneven pacing, particularly in Mimi’s sections. A NetGalley reviewer wrote: “I wanted more from Mimi’s perspective – her grief was compelling but her present-day search felt underdeveloped” . However, most agree the payoff justifies the buildup, with the final 100 pages described as “unputdownable”. The audiobook narration, featuring distinct voices for each character, has been particularly praised for enhancing the emotional impact.

About the Author

Emma Nanami Strenner is a Japanese-American writer whose work explores diaspora identity and intergenerational trauma. While biographical details are scarce (this being her debut), her nuanced portrayal of adoption and immigration suggests personal familiarity with these experiences. Strenner’s background in community organizing shines through in Sabrina’s internship scenes, which accurately depict the grind and rewards of immigrant advocacy work.

Strenner joins a wave of Asian-American authors like Celeste Ng and Jean Kwok (who blurbed the novel) exploring similar themes. However, her focus on adoption within Asian communities sets her work apart. As she stated in an interview: “Adoption stories often center white savior narratives – I wanted to show the complexity when the adoptee is racialized differently from their parents” . This perspective makes My Other Heart particularly valuable in contemporary literary conversations about identity.

Memorable Quotes

“Home isn’t where your ancestors are buried. It’s where people miss you when you’re gone.”

—Sabrina’s realization during her internship, challenging romanticized notions of heritage

“I wanted Japan to explain me to myself. Instead, it showed me how American I really was.”

—Kit’s journal entry after a month in Tokyo, confronting her cultural expectations

“A mother’s love isn’t in the blood. It’s in the keeping of promises.”

—Mimi’s reflection after seventeen years of searching